Polk at 50: A Conversation with Matthew Polk

Article written by SARAH JONES

Back in 1972, Matthew Polk and a maverick team of big dreamers with $200 to their names embarked on a wildly ambitious adventure to bring engaging, immersive sound experiences within reach for everyone. It was uncharted territory, but they never looked back in their relentless pursuit of that sonic ideal.

As Polk celebrates its 50th anniversary, I sat down with Matthew Polk to learn how the Polk sound came to be, how the challenges and rewards of loudspeaker design have evolved over the decades, and what “Great Sound for All” means today.

Take me all the way back to the beginning, that first spark of an idea.

The very first day of freshman-year orientation at Johns Hopkins, I run into this guy, George Klopfer. To be honest, I was just a nerd from suburban Philadelphia. I'm not sure I'd even ever been on an airplane at that point. George is like this Euro brat: all dressed in black, in a turtleneck, with his cigarette glued to his lower lip. For some reason, we just hit it off as friends. We were always kicking around ideas for being in business. I was already a real audio hobbyist and building my own systems.

How young were you when you discovered an interest in sound?

I think it probably started when I was six or seven. That's when I built my first kit radio with my father. He did most of the work, let's be honest about that, but that introduction to audio and electronics stuck. Through high school and college, I was always experimenting whenever I could.

When we graduated from Hopkins George and I went our separate ways. I went into graduate school; I had the idea to take my degree in physics and go into marine biology. I thought they were going to need people from the hard sciences who could design experiments.

I was right, except for one thing; I just hated marine biology. Meanwhile, George came back through town. I said, "George, what are you up to?" He said, "Well, I got fired from another job." Which will not surprise anyone who knows him. I said, "I'm in grad school, but I hate it." He said, "Well, let's do something else."

We had gotten together with some friends who were promoting bluegrass conventions. They wanted my advice on sound systems to purchase because they were always renting them. So, I'm telling them what to buy and George interrupts and says, "No, no, no. We'll build a system for you." Later, I said, "George, I can design the speakers and stuff, but we don't have a shop to work in. Is this really a good idea?"

He says, "I've got an idea." He signed us up for an adult education class in woodworking, for $2. We “acquired” some materials and borrowed a truck. We drove out there, sat down and listened to the safety lectures and stuff. People picked their projects: bird houses and mailboxes, things like that.

So, we pushed everybody away from the table saw and started running sheets of plywood through. Eventually, the instructor came over and said, "You boys aren't doing commercial work here, are you?" "No, sir. We're big audiophiles. These speakers will barely fit in our house, but the sound’s going to be fantastic.” We were invited not to come back, but we did get everything ready to assemble. And, we actually built the system and delivered it.

Then, we learned a very important business lesson when our customers couldn't pay us for it.

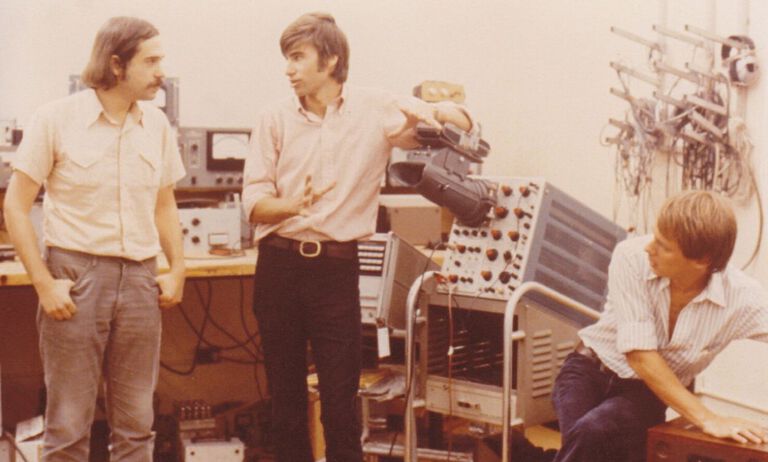

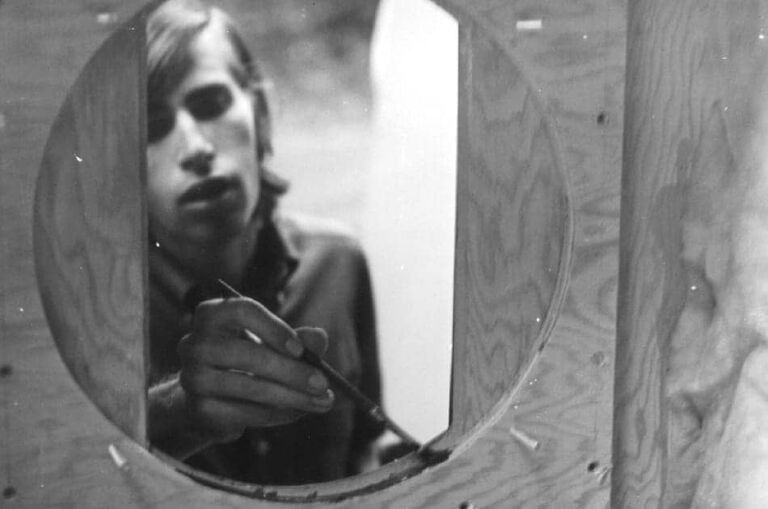

Building an early prototype

Were you initially thinking you wanted to get in the P.A. business?

Well, I just love audio. This was an opportunity to do something really interesting and challenging. When our friends couldn’t pay for the system we became de facto partners using the system for bluegrass conventions and renting it out to other people.

Some local bands liked the system and got us to build one for them. We actually had a nice little business doing that, but it was difficult because every system was different and had to be designed uniquely.

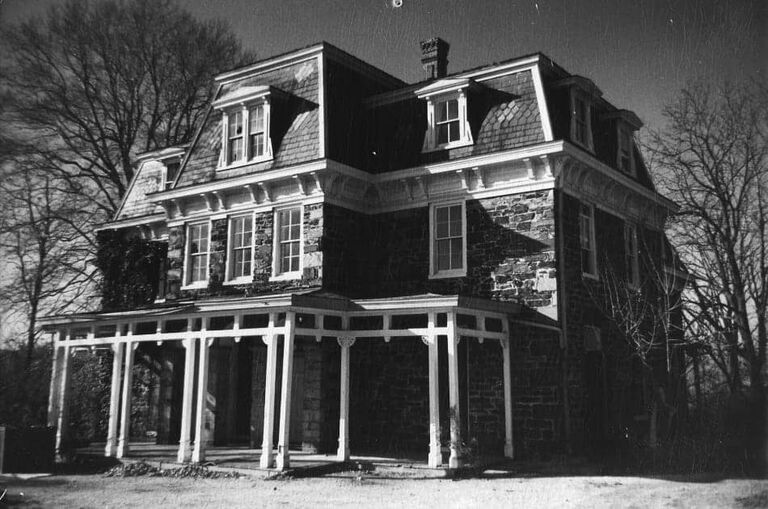

About that time, another friend of ours from Hopkins, Sandy Gross, was looking for a place to live. We were living in Baltimore in a big, decrepit old house in a bad section of town. It looked like the Addams Family house. We had plenty of room and just needed more people to dilute the rent payments. So we said, "Sure, Sandy, come on."

Now, Sandy was a genuine audiophile. He had actually been able to acquire really good equipment to listen to. That would be a benefit. So, I said, "Look, are you interested in joining us in this business?" He said, "Well, only if you're willing to look at consumer electronics and high-quality, audiophile-type loudspeaker products."

I said, "Absolutely, because then you design it once, make lots of them, and continue to refine the design, as opposed to designing something new from scratch for each customer." So we all lived and worked in this Addams Family house and in many ways it was perfect for us. It was big, 20-plus rooms with high ceilings, very cheap, and in that neighborhood no one cared if we made lots of noise or stayed up late listening to loud music. The front entryway was the warehouse and the side parlor was production. The other side parlor was the office and the dining room was quality control. My lab was up on the very spooky top floor. But most of the place was still lit with gas and had no electricity. The wood shop was next to the outhouse. It had been built in the late 1700s by a family who made a fortune selling something called Cherry Pepsin. I guess they were suspicious of modern innovations.

Polk’s first headquarters in Baltimore

Sounds medicinal. Did you all live in the house at this point?

Officially, there was Sandy and his wife, and me and George, the bachelors. Then Craig Georgi, our fourth partner. There was a rotating group of other roommates, mostly musicians—but really, anybody who could help pay the rent and who didn't mind living in a small factory. However, it was here that we developed our basic philosophy of sound and design that has remained a foundation of Polk products ever since.

You were formulating the philosophy of Great Sound for All. Why did you go that route instead of taking an esoteric, money’s-no-object approach?

Well, simply because I thought to myself, "What's the challenge of cost-no-object products?" The real challenge would be to deliver a great truly audiophile experience at a cost that most people can afford.

At that time the sound of loudspeakers had regional and national styles. The British loudspeakers had wonderful midrange and were very detailed, but the bass was bloppy. If you tried to play them loud, they would just go up in smoke instantaneously. Speakers from the West Coast of the United States, JBL, et cetera, as well as the Japanese products at the time, had an edgy, brash sound; midrange was not even really a factor, as long as it had plenty of zip and punch. The New England sound with AR and Advent was very smooth, nothing happening here.

We felt something was missing. Why couldn’t we make speakers that did it all, that could deliver a really complete listening experience at a reasonable price? As is the case with many companies started by people who are passionate about something, it's those formative years that really create a foundational philosophy. Now, we didn't sit there and say, "We need a foundational philosophy, which will continue for 50 years." What was much more on our minds was how to deliver the kind of experience that we wanted for ourselves. And, of course to be able to pay the rent next month or maybe go out for lunch at the IHOP across the street.

Order the extra bacon.

Order the extra bacon, exactly.

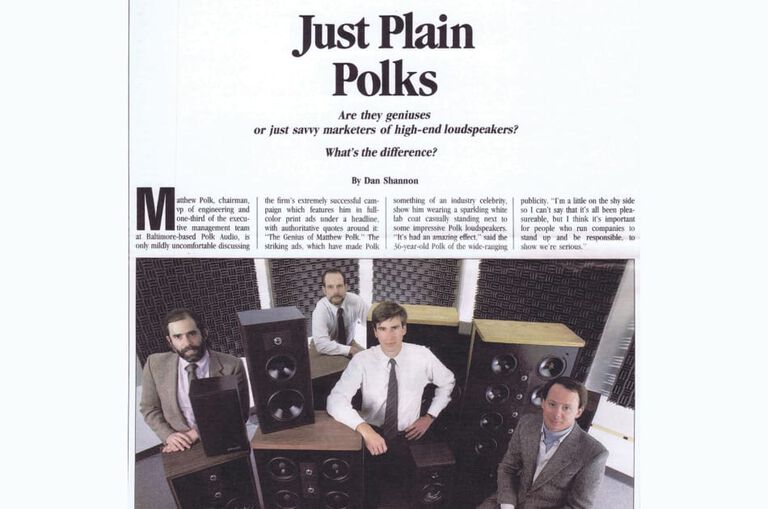

Business grows—and the hi-fi media takes notice

When did you know that you were onto something special?

Well, I think certainly the turning point was the Monitor 7. The Monitor 7 was really the first product where we felt like this is really an embodiment of what we want.

We had showed it to a few people in New York and locally in Baltimore. Soundscape, which is still in business, was our first dealer and got a very good reception. They got it. They said, "This is a product that in many respects combines the best of what European speakers have to offer in terms of purity of midrange, the ability to reproduce voice, but still has enough of the other stuff that you can have fun with it.”

I think we all felt that at that point, "We really have something here." Sandy Gross and his wife got in his old Volvo station wagon and said, "I'm going to go out and try to get us some more distribution nationally.”

They started driving across the country. Sandy would get to a town where he thought there should be a hi-fi dealer. That's what they called them back then. He would stop at a phone booth, open the yellow pages, look for a hi-fi shop, call them up and say, "I'm Sandy Gross from Polk audio. Would it be okay if I stopped by and demonstrate our new product?" They'd say, "Yeah, sure."

He did that for several summers; that Volvo had way over 300,000 miles.

It sounds like the timing was right for him to be able to pull off a grassroots movement like that.

Well, remember, this is a period of time when there're no computers and there're no smartphones. There's no internet, there're no CD players, VCRs or DVDs. Entertainment options were pretty limited. It's like your transistor radio and that's it, and your hi-fi.

Hi-fi at that time was really just beginning to be something that was accessible to a lot of people. This was really the start of the modern consumer electronics industry, in a way. It was very exciting. Everything was new. Somebody comes out with a new receiver, a new amplifier, a new turntable, a new cartridge. And, there was no lack of just weird stuff out there.

It was a new form of entertainment and you had a product that appealed to a very broad range of people.

There were established competitors who were much further ahead than us. We were lucky enough to conceptualize a niche that was available. Sandy coined the phrase, “Incredible Sound, Affordable Price,” which captured it perfectly. That also became our first real advertisement.

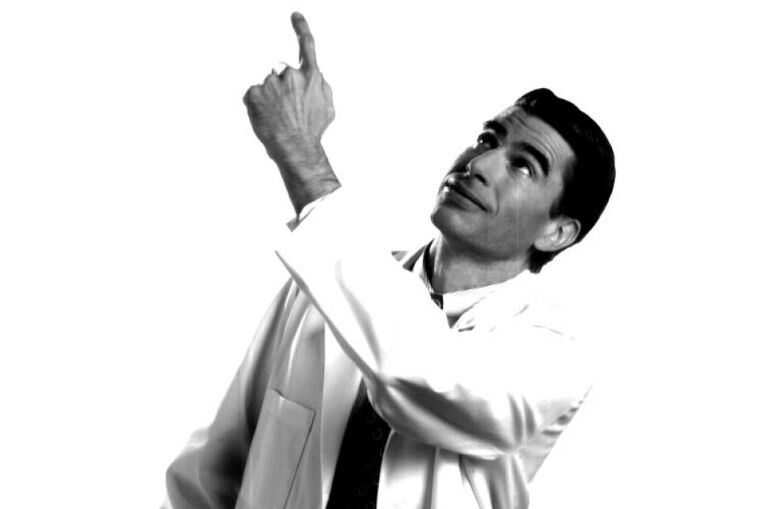

Polk in the famous lab coat

The company grew fast, and grew exponentially. What would the 1972 version of you be most surprised to know about the current climate and the current state of Polk?

Well, that the company still exists. That it's still making products that I can be personally proud of. Let me tell you, I am really proud of what everyone has done, and listening to our new 50th anniversary special-edition Reserve R200AE speaker, that was really a treat.

It sounded good in a way that really made me smile. The thing that was always most important to me was whether a loudspeaker could produce voice in a way that delivered an involving listening experience.

You bring up an interesting point about critical listening, of active listening. Polk came of age alongside the audiophile movement. With the convenience of digital technologies and ease of access to high-res streaming and immersive platforms like Atmos, are people paying more attention to sound today?

Certainly, as a percentage of the population, more people listen to music now than ever before. But, I think fewer people listen critically than they did back in the '70s and '80s. Really the turning point came in the mid-'90s as digital music displaced analog music.

Cost, convenience, and access will trump performance, all day, every day for most people. That said, there do seem to be more and more people now who are actually looking for a real experiential relationship with their music. They're saying, "I'd really like to have the kinds of experiences that I had back in the '70s or '80s when I was listening to music. It was really exciting and involving."

In some cases it's younger people who are just discovering that this kind of thing exists, what a vinyl record sounds like, what a really good hi-fi system sounds like. They're amazed at this fantastic and genuine experience. As you know, authenticity has become more and more important to people in the activities that they pursue and the products that they buy. A good music listening experience really offers that kind of authenticity and involvement in a way that few other things can.

With modern technologies and materials innovations, is it easier to build a better speaker nowadays?

I do think it's easier to design a fundamentally decent-sounding speaker now. It's also much harder to design a bad one. You have inexpensive measurement tools available; you have inexpensive computer design tools available. I was literally using a slide rule at the beginning. Calculators were a new and expensive thing.

That said, whenever you're designing a piece of audio gear, you're reproducing a signal. As soon as you say the word “reproduction,” it can never be identical to the original performance. To some degree it will always be an interpretation. Polk Audio, I'm happy to say, still delivers an interpretation that brings joy and involvement to our customers’ listening experience.

Loudspeaker design is mostly science, but there's some art to it; aspects you might quantify in different ways.

That's an important point to make, yes, there is a lot of science and engineering to it, but if you stop there you're really not going to deliver for your customers. You have to go past that to the art side. It's a difficult transition to make. If there's one thing that we did very successfully as a company, we were able to make that leap consistently, and still do.

What comes to mind when you think about five decades of Polk?

In one respect, I'm amazed and thankful. In another respect, I never had any doubts. Of course, Polk Audio is still here 50 years later because I think that our goals have been very genuine in terms of what we have wanted to do for people.

My buddy George used to get up in front of everyone at the company meetings. He'd say, "What are we here for? Are we here to enrich the shareholders or to create a place where people can work and grow?" It would be like a food fight, of course.

He'd say, "No, we're only here for our customers." Everybody would get really quiet because he was absolutely right. It's the only reason we're here.